Defining Highways:

Regionalism, Routes and Circuits in American Road Literature

Sample

Introduction: Origins, Asphalt, and Exits

“As often as not, we are homesick most for the places we have never known.”

- Carson McCullers, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter (1940)

Popular twentieth-century United States fiction and travelogues typically treat the development of the national highway system as anathema to the discovery and preservation of cultural regionalism and local color. As each evolution of the nation’s superhighways has enabled and encouraged faster automobile travel, nostalgia-seeking travel texts have taken issue with how inimitable, local places are increasingly passed over, and how an emphasis on accelerating personal mobility pushes Americans to forsake the familiarities of home for the potential of the open road and its linked destinations. Charles Kuralt lamented the completion of Interstate 40 (which replaced much of Route 66 in the Southwest), admitting “it is now possible to travel across the country from coast to coast without seeing anything,” and this disillusionment inspired him to pitch the nostalgic, backroads-seeking weekly CBS news feature “On the Road.” Perhaps most explicitly, William Least Heat-Moon’s Blue Highways: a Journey into America describes the national wonders to be discovered if the cross-country driver simply sticks to the local roads marked in blue on the Rand McNally Road Atlas instead of racing by the countryside via the highways (marked in red). “Defining Highways” argues that the development and expansion of national and Interstate highways actually spurred, rather than obscured, various forms of regionalism by shaping communities into destinations to be mapped, visited, documented and commodified. Instead of existing in isolation, locales and regions must be understood in dynamic relation to the national roads that lead into and out of them.

Brochure for Kansas’s I-70 corridor – “America’s Main Street”

Whether winding along the Big Sur coast (California Route 1), connecting Colorado mountain towns (the Peak to Peak Highway), or linking a series of Walmarts and chain restaurants (Interstate 70 in Kansas; America’s “Main Street”), highways are places in and of themselves. Highways may allow drivers to efficiently bypass and obscure existing local features and communities; yet, this redirecting does not necessarily eliminate regional culture as much as it transforms fixed places into living circuits that progressively assume the character of their users. Joan Didion renders a vivid example of this phenomenon in her 1970 novel Play It As It Lays, as her protagonist Maria Wyeth responds to her partner leaving and the sudden emptiness of her home by rushing out each morning to inhabit the Los Angeles freeway:

Maria drove the freeway. She dressed every morning with a greater sense of purpose than she had felt in some time. […] For it was essential (to pause was to throw herself into unspeakable peril) that she be on the freeway by ten o’clock. Not somewhere on Hollywood Boulevard, not on her way to the freeway, but actually on the freeway. If she was not she lost the day’s rhythm, its precariously imposed momentum. Once she was on the freeway and had maneuvered her way to a fast lane she turned on the radio at a high volume and she drove. She drove the San Diego to the Harbor, the Harbor up to the Hollywood, the Hollywood to the Golden State, the Santa Monica, the Santa Ana, the Pasadena, the Ventura. She drove it as a riverman runs a river, every day more attuned to its currents, its deceptions, and just as a riverman feels the pull of the rapids in the lull between sleeping and waking, so Maria lay at nights in the still of Beverly Hills and saw the great signs soar overhead at seventy miles an hour. Normandie ¼ Vermont ¾ Harbor Fwy 1. Again and again she returned to an intricate stretch just south of the interchange where successful passage from the Hollywood onto the Harbor required a diagonal move across four lanes of traffic. On the afternoon she finally did it without once braking or losing the beat on the radio she was exhilarated, and that night slept dreamlessly. (15-16)

Despite only stopping for gas between when she pulls out of her driveway in the morning and rolls back in at night – and speaking to no one throughout the day, Maria makes a home out of the Los Angeles freeway circuit. She understands how certain lanes bend and merge, and she recognizes the driving patterns of her fellow highway travelers. She maps out the surrounding roadscape based on particular intersections that, though not marked by iconic corner stores or crossroads saloons, possess unique characteristics and challenges that give her day a sense of fulfillment. From afar, the L.A. freeway may resemble little more than endless concrete, asphalt, and lane shifts, yet Maria is definitely spending her days within a dynamic regional space. As she moves among the freeways that, rather than offer landmark-based destinations or exits, serve as satellites charting the range of her driving, she internalizes the L.A. freeway so intensely that she still sees its signage when she looks out at the sky from her Beverly Hills home. Like walking city streets or a grueling hike through magnificent landscapes, driving the freeway gives Maria a thrilling sense of momentum when her life has otherwise become depressingly stagnant.

In Play It As It Lays, Joan Didion suggests that endlessly driving the L.A. freeway is a problematic substitute for other forms of personal mobility. Maria Wyeth drives each day, not to improve her socioeconomic standing, but simply to go, and to not be home. Play It As It Lays is a haunting novel. Its overwhelming alienation and desperation result from taking an unremarkable routine – navigating a city highway – and making it a way of life. In 1970, when the U.S. Interstate System was just over a decade old, Didion uses her novel to comment on how Southern California freeways have dramatically and terrifyingly altered the region’s landscape. Maria recounts each successive highway she travels with a nonchalance that suggests the regularity of her driving schedule; yet, her language – “the Hollywood to the Golden State, the Santa Monica…” – is still packed with meaningful coordinates for a Los Angeles local. This is Didion’s unsettling point: Maria is a well-connected socialite and she knows the city as well as anyone, though the highway is the only place where she feels alive and part of something with any discernable momentum. Play It As It Lays challenges its readers to accept the Los Angeles freeway circuit as a regional space that is so central to the lives of its users that its anonymity and transience necessarily permeate their lives.[1] A half-century later, the freeway continues to singularly unite Los Angeles’ many individual neighborhoods and it has become so essential that the majority of its drivers will sit in bumper-to-bumper traffic rather than risk “getting lost” by exiting the highway and attempting to maneuver local side streets.[2] Such commitment to the freeway persists because U.S. highways, despite increasing congestion and monotony experienced by drivers (like Maria Wyeth), continue to represent national expansion, produce unique cultural circuits, and facilitate individualistic escapes from hegemonic modes of everyday life. “Defining Highways” argues that the nation’s iconic “superhighways” – first wagon roads, then transcontinental railroads, and finally high-speed autoroads – each uniquely transformed how Americans understood the relationship between their local roots and evolving travel routes.

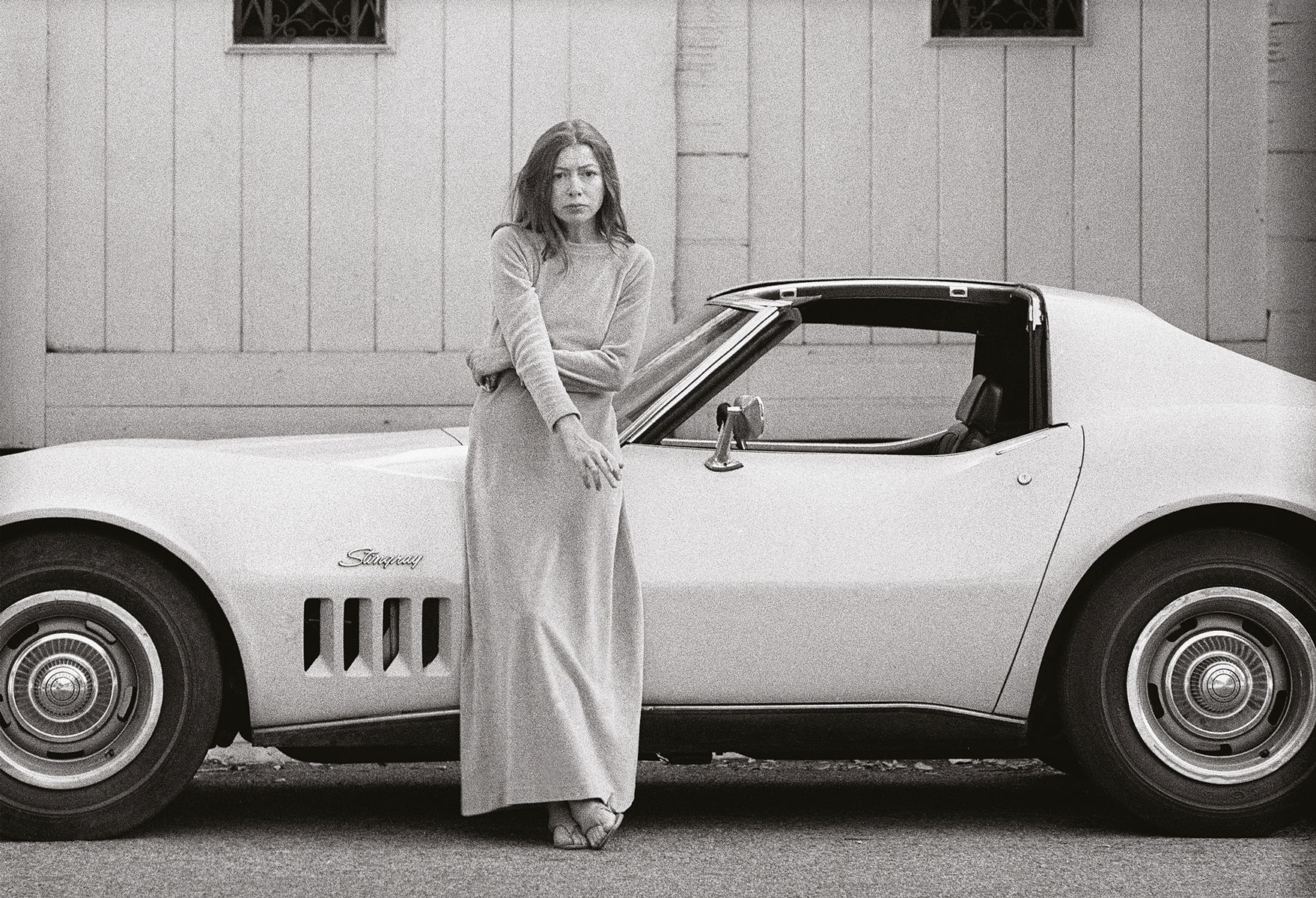

[1] Didion also felt the importance of automobile and highway culture in her own life, as her favorite collector’s item was a Corvette Stingray. An image of her in the driver’s seat (from the same 1968 Time photo shoot) is on the cover of her 1979 collection The White Album.

[2] Recently, Los Angeles was again recognized as having the nation’s worst traffic. The city’s average driver “sat in traffic for an average of 90 hours in 2013, and for every hour commute driven in peak periods, suffered 39 minutes of delay” (http://time.com/2821738/los-angeles-traffic-study/). This study specifies that those driving in peak Los Angeles traffic actually sat in their still cars for longer than they spent in motion during their commute. Thus, while the freeway encourages fast-paced movement, most rush hour commuters find themselves occupying a series of stationary positions within the city as they stop and go through frequent gridlock.